Sonia Levy: For the Love of Corals

25 March - 6 May 2021

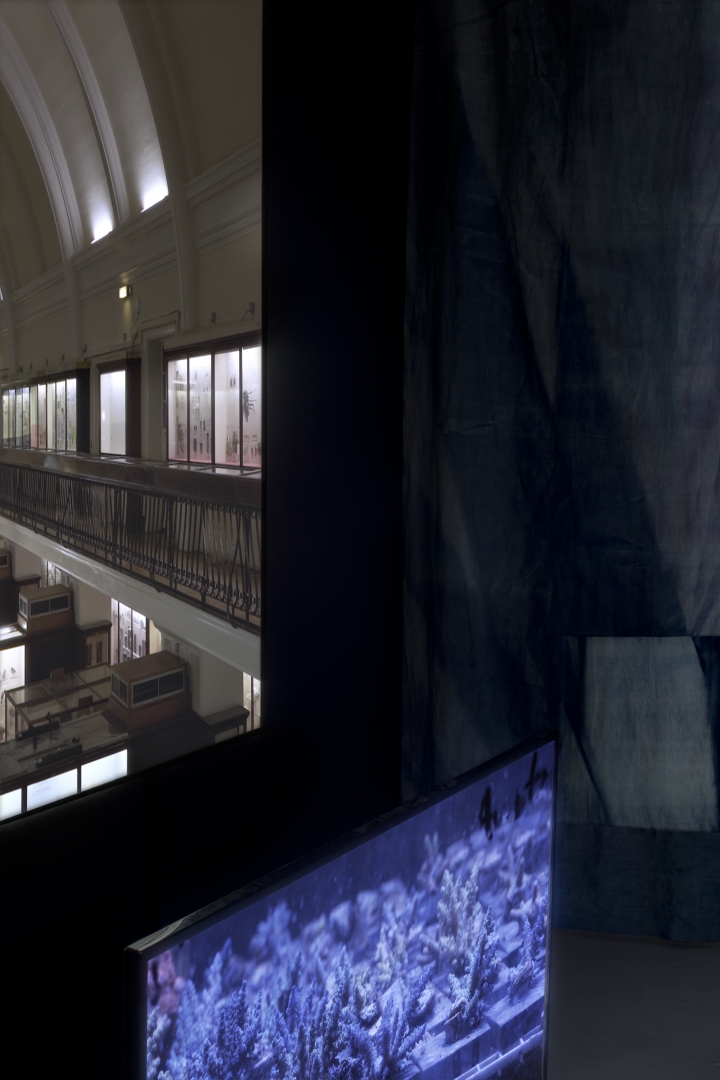

Karlin Studios / FUTURA Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague

In an age when biologists push their research to its limits – by using computer simulation to model living things, by scouting for extreme organisms in sea and space, by seeking to synthesize new life forms in laboratories – the definition of “life” is becoming unfastened from its familiar grounding in existing earthly organisms. The relation of life to possible materials, circumstances, and processes is multiplied, moved toward uncertain limits.1

What is life? According to biologist and pioneer of symbiosis Lynn Margulis, life is a chimeric process, a gathering and compounding of creatures into new assemblages. In her approximation2, living things are those that grow and multiply. Life is a pulsating collection of cells that separate inside from outside through a semi-porous membrane. They create copies of themselves and construct their own scaffolding structures. Occasionally they merge with one another with far-reaching consequences. In this sense, life describes multiplying entities that breathe, love and consume.

From water, light, oxygen and carbon dioxide, all living beings were able to grow and colonise this planet. We are implicated in all of them through water that courses through and replenishes us in waves and swells. Liquidity is an immersive experience of being-in-the-world together with other species. This rhythmic dance of particles and cells in the ocean comes to its crescendo on a moonlit night when once a year corals spawn in unison. Life reverberates as the tiny egg and sperm bundles float away with the ocean currents. They find one another and create new life in an ecological orgy. Through the spawning, a large web of relations unfold and new sorts of corals come into being through the process of recombination and hybridization. As the corals find their footing on rocks, it is the beginning of something bigger: they are not only themselves symbiotic, but their structures will eventually constitute environments for a large variety of other beings contributing to all surrounding ecosystems.

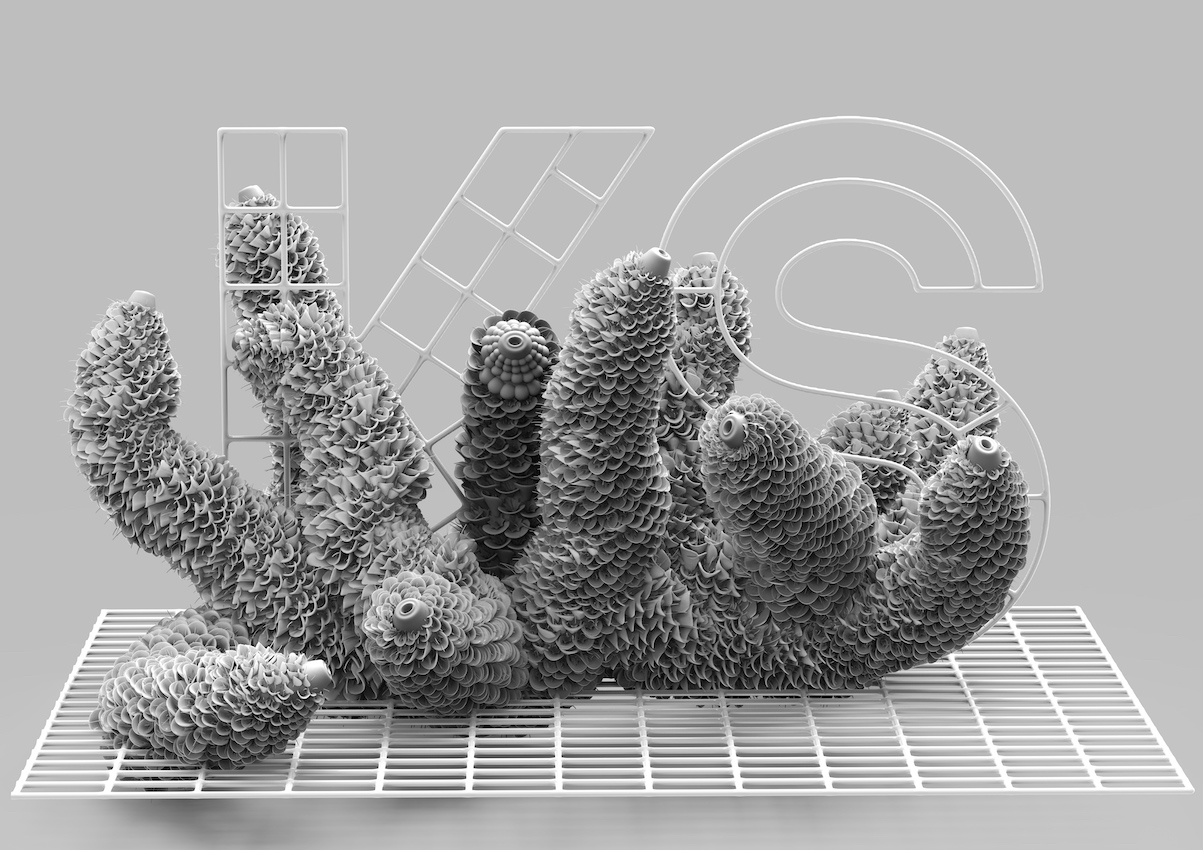

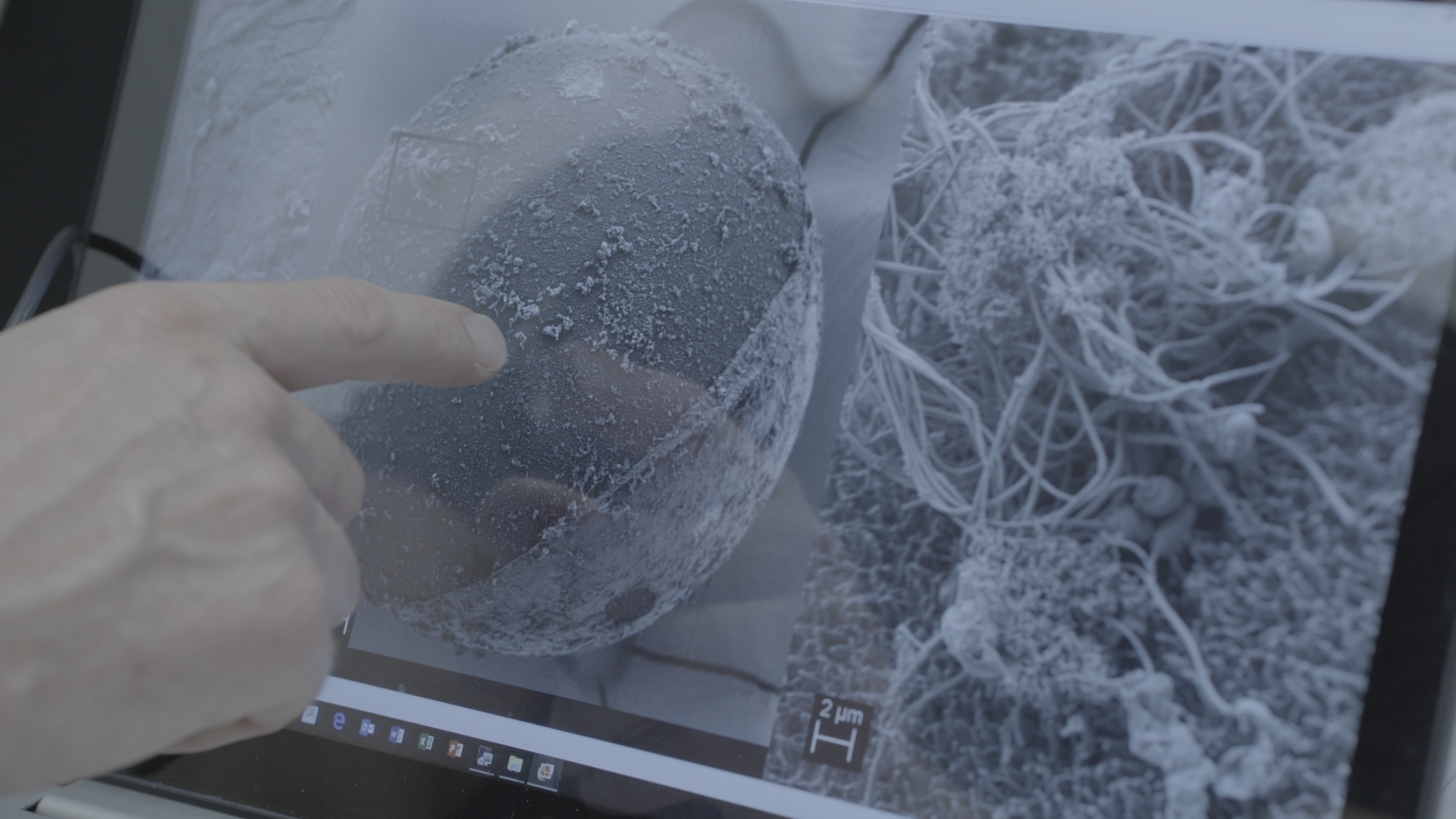

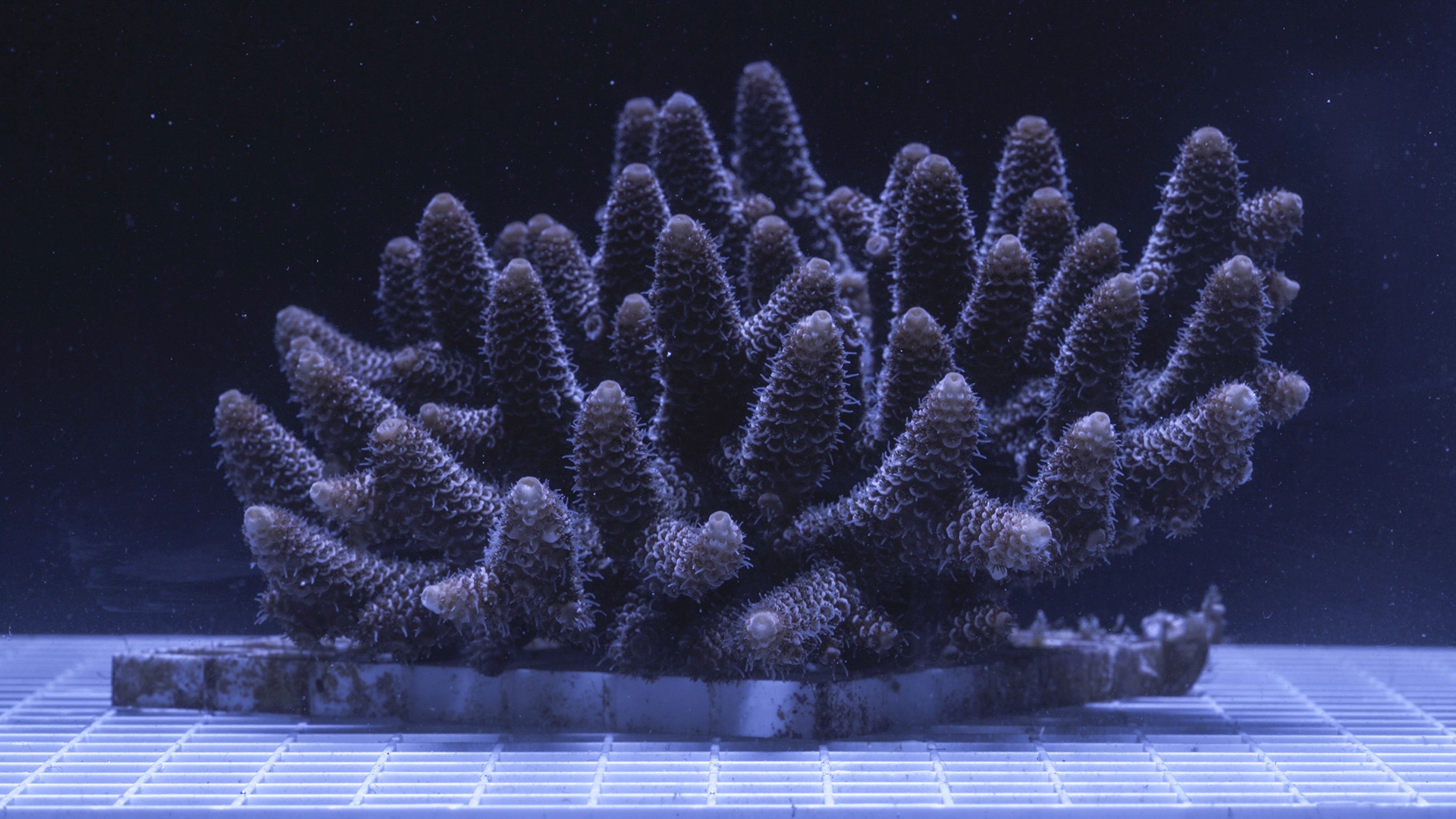

Sonia Levy’s For the Love of Corals is a case study that documents the techniques of care employed by the scientists to successfully induce coral spawning in a laboratory for the first time. To find out more, we go underground and behind the scenes of the Horniman Aquarium in South East London. Here, in a series of small, but highly specialised tanks, Project Coral is a pioneering research project led by marine biologist and aquarium curator Jamie Craggs. The context of the aquarium is the Horniman Museum and Gardens, where, in many ways, the Victorian and colonial heritage and values of human mastery over nature are still encoded in the historic displays. Levy examines how a living collection within this museum can however become a base for a research project for collaborative multispecies survival.

Simulating the environmental conditions of the Great Barrier Reef in the small laboratory, the chatter of the reef is replaced by the constant noise of pumps and other electrical devices. Instead of the light of celestial bodies, lamps mimic the sun and the phases of the moon. Coral IVF happens through both highly specialised devices and basic DIY tools, however, these technological infrastructures alone wouldn’t be enough. As revealed by Levy’s film, the most important are the intimate knowledge and care of the scientists. Through paying close attention to corals, Levy’s cinematic inquiry subverts the categories of animal, vegetal and mineral as well as nature and culture and bridges them by providing fertile ground to speculate about responsibilities and the importance of acts of care and relationships for future landscapes.

Corals are especially vulnerable due to the human-induced climate crisis, pollution and exploitation of the oceans, and they are quickly disappearing. Hence research into possibilities of saving them, including potentially creating more resilient individuals that can withstand higher levels of ocean acidity is pressing. It is important work, even though the re-introduction of corals is at best a patchy solution and no substitute for the much-needed systemic change.

As part of the installation and accompanying Levy’s video piece, a large cyanotype tapestry echoes Anna Atkins work. In the 19th century, the scientific world was dominated by men, and botanical collections and illustrations were some of the few acceptable ways for women to engage with such subjects. Featured in Levy’s film, a surviving copy of Atkins’ pioneering collection of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is kept at the Horniman Library. Published in 1842, it is the first book to be illustrated by photographic images. The beauty and simplicity of the seaweed images are captivating as they document not only a large biodiversity but the processes and knowledge involved in collecting, handling and arranging them. Cyanotype images were especially fitting for her project as they document a direct physical connection with the plants each time, while they also require exposure to sunlight and submersion in water, much like the seaweed themselves. Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes are surfacing today – a time defined by species’ loss, ecological collapses and political turmoil. Their re-discovery is a call to revisit our past, the stories we inherit, and the ones we now want to tell our world with.3

Bio

Sonia Levy is a French artist based in London. Her research-led practice engages contemporary socio-ecological urgencies at the intersection of art and science. Through this co-becoming of disciplines, she uses filmmaking to query science’s history of entanglement with western colonial extractivist logic. Her work attempts to develop new practices of care, fostering dialogue as a means to consider new worlds.

She is a 2021 commissioned artist at Radar Loughborough and Aarhus University's Ecological Globalisation Research Group. She was a participant in the 2020 Artquest Peer Forum 'Rewilding’ at the Horniman Museum and Gardens. She has exhibited in the UK and internationally including shows and screenings at Centre Pompidou, Paris; Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris; ICA, London; BALTIC, Gateshead; Obsidian Coast, Bradford-on-Avon; Goldsmiths College, London; The Showroom, London; Pump House Gallery, London; ZKM Karlsruhe, Art Laboratory Berlin; HDKV, Heidelberg; Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cambridge MA; Verksmiðjan á Hjalteyri, Iceland and The Húsavík Whale Museum, Iceland.

Her work has been published by MIT Press, Antennae Journal, The Learned Pig, Billebaude, Verdure Engraved, and has appeared in NatureCulture and Parallax journal. She recently presented her research at NYU Gallatin, New York, The University of California, Santa Cruz, The Iceland Academy of the Arts, The Oslo School of Environmental Humanities, Trondheim Academy of Fine Art and AURA: Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene.

1 Stefan Helmreich, Sounding the Limits of Life. Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond. Princeton

University Press, 2016.

2 Symbiotic Earth: How Lynn Margulis Rocked the Boat and Started a Scientific Revolution is a feature length

documentary film directed by John Felman, 2017.

3 Sonia Levy, Anna Atkins; Sun-Pictures & Ghosts of the Anthropocene, French version published in Billebaude

N°12, Cueillir, Ed. Anne de Malleray, Glénat, 2018